The History of the Kilt

The Past

We're not entirely sure exactly when the beginning was, but a few things we know for certain:

There's a few things we know for certain:

- The oldest fragment of tartan in Scotland today, is around 1200 years old. It's known as the Falkirk tartan simply due to the fact it was found there.

- Although Scotland has made tartan what it is today, it cannot take responsibility for its invention - criss-cross fabrics had been woven by indigenous people across the world for an incredibly long time.

- Kilts were widely adopted as what we would recognise as the Great Kilt, or Feileadh Mor or belted plaid, from around the mid 16th century.

- The tailored kilt, the likes of which you will recognise from our own range, was invented in the 1720s by Thomas Rawlinson - yes, and Englishman hailing from Lancashire.

- Finally, no we don't know what's under the kilt, that will forever remain a mystery, but the other accessories have remained rather untouched for centuries...

The exact origins of the kilt are a little harder to define. There's a number of possible ways the Great Kilt reached Scotland and developed, such as:

- Irish Gaels preaching Christianity to the Pagan Scottish tribes may have worn a garment of heavily draped wool which influenced the people of Scotland to take to wearing their handmade cloth in such a way.

- Roman occupation was famously short in Scotland as compared to the rest of Great Britain, however, they may have been here long enough for the toga to inspire the Scots.

Early kilts were made of very coarse wool. The cloth was made locally, sometimes in the very home of the wearer, sometimes by a travelling weaving in more affluent communities. District tartans pre-date clan tartans considerably due to the dye stuff for yarns being gathered around the area people were living, and thus the cloth reflected the land. Women of the community would gather, spin and dye the yarn, as well as eventually weaving it for many centuries before looms began to develop and modernise into the more industrial beasts of machines similar to what we see today.

Next period

1500s

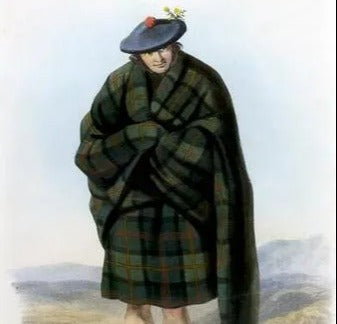

By the 1500's the Feileadh Mor was the dress of choice (forget what you've seen in Braveheart set in the late 13th century). Worn largely by the rural highlanders working on the land and, over time, nobility also, the kilt was a multi-functional garment. It was made from cloth with a waterproof quality, twill woven wool is idea for the unpredictable Scottish climate; it was pleated which kept heat in and the body warm; and it could be worn as camouflage in the very terrain which dyed it, and even a sleeping bag style shelter.

So what was the Great Kilt?

- A woollen garment comprising of about a 5 yard by 5 yard, more or less, square of cloth

- Loosely pleated by hand every wear, no sewing or tailoring was involved at all

- A belt was used around the waist to keep the kilt up - hence "belted plaid"

- From the belt hung a sporran, a pocket substitute it you like comprising of the Highlanders wordly possessions and...oats for lunch, a dirk derived from a broken sword before coming into its very own as a staple of the Highland wardrobe

- The excess of the cloth would either be left to freely hang around the claves, be tied up at the shoulder out of the way or wrapped around the shoulders to keep warm or hidden...

1700s

Kilts - A Symbol of Hope For Some & Rebellion For Others

Kilts took on a very different meaning in 1745. Once just the common dress of the Scottish Highlander, the kilt and the tartan it was made from. 1745 marked the final Jacobite rebellion against the Hanoverian Crown, lead by Charles Edward Stuart, son of James VIII & III, the exiled Stuart King to some and "Old Pretender" to others depending on your persuasion. Tired of red coats rule over the land and wishing to restore a sympathetic Catholic Stuart to the throne of Britain once more, many Highland Clans put aside their ancient differences, and joined the Bonnie Prince in his campaign against the Government forces. This was not as simple as the medieval battles of Scotland versus England (and this certainly wasn't the case in regards to who fought on each side either), this was political, religious and personal with families at the root of the army on one side.

The '45 began successfully. Charles managed to bring was warring men together to fight under the Jacobite banner. They experienced a number of successes against the Red Coats, such as Falkirk, Prestonpans and laying siege to the City of Edinburgh. The marched to within 120 miles of London, the goal, but failed to muster support from Northern England or reinforcement from France. They turned back - exhausted and morale at an all time low, they marched from Derby to Inverness where they finally set up camp near Culloden Moor, the Government forces not far behind lead by the Duke of Cumberland.

Battle weary, the Jacobites took a final stand on the 16th April 1746 and were defeated in an hour by the Red Coats in a truly bloody battle. Charles Edward Stuart evaded capture for months, and finally fled Scotland to return to Europe - he never returned to these shores again.

The battle was decisive and the Hanoverians wanted to silence all whispers of another attempt on their throne. The highlanders had to be punished, and they were so - through the Acts of Proscription and the Dress Act of 1746, the Highland culture was virtually eradicated. The playing of bagpipes, the speaking of Gaelic, the wearing of kilts and tartan were all effected. What the Highlanders held dear was now only permitted if you were part of a military regiment. The landscape once awash with swirling kilts and intricate tartans was bare...for 37 years.

Another man now comes into the picture...not a prince but an author. An author who saw all of the beauty and drama the highlands and its rich culture had to offer, which was missed so dearly. The infamous words of Walter Scott put Scotland back on the map again. It's icons and customs now celebrated rather than condemned. Scott was held in such high regard thanks to his incredibly popular novels all set in his homeland such as Waverley and Rob Roy, that people couldn't get enough - the appetite for kilts and tartan was reinvigorated at a rate and to an audience never before seen.

Scott was tasked with orchestrating the visit of King George IV to Edinburgh in August 1822 - the first Hanoverian monarch to ever visit this part of his nation and the first monarch at all to visit since 1633, the Coronation of Charles I. This visit was a celebration of great importance, Scotland was being brought back into the fold of the United Kingdom. It was a display of the finest tartans - weavers Wilson's of Bannockburn were producing tartan, tartan that had never been seen before using dye stuff that wasn't available pre The Dress Act of 1746. They were vibrant, exciting and based on Clan. Chief's were invited to choose a sett they liked or perhaps develop a fragment that had survived proscription. George IV himself adorned himself a complete highland garb in an outfit worth anywhere between £10,000 to closer to £1million according to different sources, in today's money. He was ridiculed by some and the gesture appreciated by others - Scot's not best known for being able to agree on anything.

1800s

The Royal Attire - Balmoralisation

This incredible appetite for kilts and tartan continued through the Victorian era. In 1842, the Vestiarium Scoticum was written and illustrated by the Sobieski-Stuarts detailing the role of Highland and Lowland clans and their accompanying tartans based on pre-culloden swatches... This book was eaten up by the Victorian's excited at such a document and believing the authors so publicly claiming to be the great-grandson's of none other than Charles Edward Stuart - Gordon Nicolson Kiltmakers actually has a copy of this ever dubious but hugely fascinating artefact, more on this another time.Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, had a huge place in their hearts for Scotland. They purchased Balmoral and made it into a Highland haven for their family and the generations to follow. Prince Albert, of Germany, even tried his hand at learning Gaelic - he didn't fair too well it's said. In her later, lonelier years, the Queen found companionship in Scots Ghillie of Balmoral John Brown and wrote fondly of the Highlands in her journals her entire life and reign. This period in the story of kilts and tartan is known as Balmoralisation. Collections of tartan grew throughout this time, the Victorian's wanted a sett and colour way for every occasion. Clan tartans developed to be not just Modern (dark) and Anicent (bright) colourways reflective of the dye matter used, but Hunting tartans were developed, Dress tartans, Mourning tartans. The tailored kilt, the uniform of highland regiments since the 1720s saw some development and steam-lining to make it even more practical.

1900s

The Final Battle - Kilts Make Their Last Stand On Front Line Battle

At this stage, the kilt is a joyous thing once more, tartan is to show a sense of belonging, it's not just worn by Highlanders but anyone and everyone with a highland connection - such was the Victorian's commercial ability, which we undoubtedly still benefit from today. But remember, the kilt had once been the uniform of the Jacobite soldier, it was the way the garment survived during the prohibitions of The Dress Act too seeing as it was permitted as regimental dress...again the kilt would find itself fighting in the trenches of World War I, adorning Scots soldiers in the Great War. This was the last time the kilt saw front line battle as it had in 1745, however, there is, on display in the Cameron museum, even a regimental kilt worn on the beaches of Dunkirk during the Second World War, in the early summer of 1940. There is a story, one which despite all of the horrors of war can actually bring a smile to our faces - a kilted soldier playing his bagpipes on the beaches of France took the enemy so by surprise at drawing such attention to himself, they actually stopped shooting, and listened to the old and meaningful tune he was playing.

Next period

The Present & Future

So we have discovered that the history of kilts and tartan is filled with drama & debate, spanning the Scottish highlands to royal courts, witnessing countless defining moments, surviving prohibition and deceptive romanticism to evolve into the globally renowned versions that we recognise today. And here we ourselves step up - but not as petty marketeers trying to cash in or make a fast profit - quite the contrary.

Our founder, Gordon, tentatively opened Gordon Nicolson Kiltmakers from very humble beginnings in 2009. He hoped to build a viable local business capable of creating enough demand and regular income to ensure the traditional craft of handsewn kiltmaking was not lost in the pursuit of profit. Since that beginning, each kilt has been made to the highest quality, tailored to last a lifetime. As our reputation grew, demand for authentically handmade kilts and highlandwear increased. Simultaneously so did the risks to our homegrown industry and its small community of makers and suppliers - caused by an influx of imported, cheaply produced, inferior goods. Gordon sensed a crisis was looming but believed there could be more to gain than loose, and so in early 2016 he opened the Edinburgh Kiltmakers Academy. Gordons intention was simple but daunting - to develop & formalise a new standardised kiltmaking qualification in order to share skills, build a workforce, bolster the industry and inspire future generations of passionate kiltmakers. His ambitious but dearly held dream was realised !

The Edinburgh Kiltmakers Academy and Gordon Nicolson Kiltmakers are now wed in symbiotic harmony - producing the finest kilts available, crafted by our skilled artisans trained to the highest standards. We are committed to ensuring that kiltmaking remains a vibrant and thriving craft, especially in light of its recent Endangered classification by the Heritage Craft Association. We believe that a kilt is not simply a piece of clothing, but an emblem of our culture and heritage. We are proud to use 100% wool tartans and tweeds expertly oven in Scotland's finest mills and to offer a wide range of beautiful tartans - some traditional and well-known, others modern & fresh - including a range of our own exclusive tartan designs. We welcome customers from all over the world who love and appreciate our culture and celebrate it by wearing our kilts. Despite ongoing challenges, including global pandemics and economic recessions, we remain optimistic about the future of kiltmaking. We are committed to protecting and promoting the craft and sharing our passion with future generations. It's inspiring to witness the enduring appeal of Scottish heritage across the globe, and we're eager to contribute to the evolution of kiltmaking in the years to come.

Back to start